MERIT HISTORY

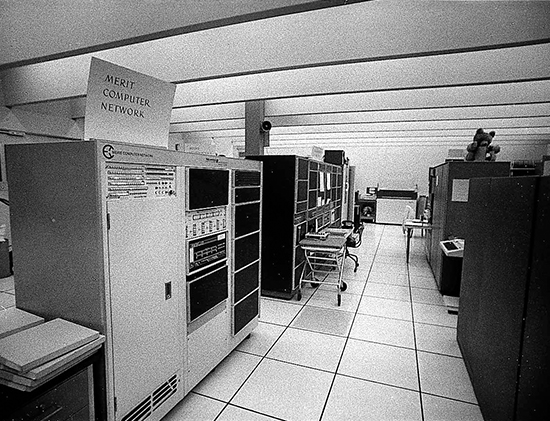

Primary Communications Processor (1981)

A HISTORY OF EXCELLENCE & INNOVATION

Created in 1966, Merit Network has been a leader in networking and internet technologies for 50 years. Founded by Michigan State University, Wayne State University, and the University of Michigan, Merit established networking in Michigan long before the term “Internet” was invented.

Merit pioneered many of the practices and protocols used in today’s Internet. Since Merit’s inception, our researchers and engineers have been instrumental in the successful deployment of many advanced networking projects, including:

- RADb: The Routing Assets Database

- BGP Tables

- Routing Arbiter Project

- Route Server Next Generation

- GateD & Authentication, Authorization, Accounting Software

- Internet Performance Measurement and Analytics

- Splitting Wavelengths

Editor’s note: This remarkable article was written in 1989 by John Mulcahy, a Merit staff member who had been hired on a temporary basis to complete a variety of technical writing projects.

The Merit Computer Network has roots in Michigan Governor George Romney’s blue ribbon committee report on higher education in 1963. That committee’s recommendations inspired then University of Michigan Vice President Roger Heyns to envision a state-wide learning center to exchange information. Heyns asked University of Michigan professor Stanford Ericksen, director of the new Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, to write a learning center proposal for the university’s 1964 legislative budget request. As part of the proposal, Ericksen’s associate Karl Zinn suggested a state-wide prototype computer network, which evolved almost ten years later into the Merit Computer Network.

Ericksen, now retired, and Zinn, still a research scientist at the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, stress that the original plan dealt more with education than computer networks. Though the legislature rejected most of the proposal, some legislators encouraged the network idea to help the state’s educational and economic development.

“The computer network idea took on a great deal of fervor,” said Ericksen from his retirement home in Florida.

In response to this legislative interest, Ericksen and Zinn helped form the Inter-University Committee on Instructional Use of Computers in 1964. That committee, which included representatives from all the state-supported schools, met for two years without making any new proposals to the state legislature, according to Zinn. Following the committee’s disbandonment, the state’s three largest schools the University of Michigan, Wayne State University, and Michigan State University formed the Michigan Inter-university Committee on Information Systems (MICIS) in early 1966. MICIS’ overall purpose was to engage the universities in the “broad area of information processing and exchange by computer and other electronic media.”

MICIS representatives included one high ranking officer from each of the universities. Allan F. Smith, a former University of Michigan Law School dean who had become the university’s vice president for academic affairs in 1965 and later served at interim president of the university, was elected MICIS’ first president. He held the position until he returned to the Law School in 1974.

Besides Smith, Milton Muelder, vice president of research development at Michigan State University, and Robert Hubbard, executive director of educational services at Wayne State University, served on the Joint Executive Council of MICIS.

Other MICIS representatives included Stanford Ericksen, James Miller, Director of the University of Michigan’s Mental Health Research Institute, University of Michigan Computing Center Associate Director Frank Westervelt, Michigan State Computer Laboratory Associate Director Julian Kateley, and Wayne State University Computing Center Director Walter Hoffman. Karl Zinn also frequently attended the MICIS meetings.

At MICIS’ recommendation, the three universities formed the non-profit Michigan Educational Research Information Triad, or MERIT, Inc. in the fall of 1966, as an entity to seek non-state funds for interuniversity computer communications. While the official corporate entity was and remains MERIT, Inc., the organization which carries out the day to day network operations is known as the Merit Computer Network. The latter name is the one commonly used today, especially since the addition of five new member schools means the network is no longer a triad.

From 1966 to mid-1969 MERIT’s parent, MICIS, struggled with the problems of defining what the new computer network was to be, finding money to pay for it, and building an organization to make it a reality. As chief financial officer for the University of Michigan, it fell naturally to Smith to act as point man in seeking state funds for MERIT.

“My role, if any, was to nurture it with money, and they elected me president so I could watch my money,” says the self-effacing Smith today from his office in the University of Michigan Law School. “It’s nice to have nurtured something that turned out so well,” he adds.

To get help in persuading the state legislature to pass a network funding bill, Smith and Miller met with Governor George Romney in early 1966. Besides a computer network, they proposed an “educational clearinghouse” and plans for better teacher preparation ideas similar to Ericksen’s and Zinn’s concepts of more than two years earlier.

An unsigned copy of a March 16, 1966 letter from Romney to Smith shows Romney interested in “meeting increased costs with technological innovation.” He promised to include over $1 million for all parts of the program in his budget request to the legislature, starting with $200,000 for “planning and coordination.”

“We did get support from the governor’s office. Not only Romney, but his successors,” Smith says. He adds that the legislature, too, was eager for ways to save money by pooling educational resources. “The idea itself just sounds so beautiful.”

On April 29, 1966 Romney Assistant John W. Porter wrote Smith that the administration was seeking $565,000 as a line item for the new program. The minutes of the University of Michigan Board of Regents meeting for October, 1966 show that the university, too, had included a network funds request in its budget proposal. The regents decided to withdraw the request in favor of one submitted jointly by the three MERIT universities, after the incorporation of MERIT in the fall of 1966.

From the fall of 1966 until June 1967 MICIS waited and debated. The legislature had not acted in January 1967, and MICIS asked Smith to contact the governor’s office to find out the state of the proposal. By February, Smith could only to discover that the Board of Education, which was supposed to evaluate the proposal, hadn’t done so. Things were hardly better in March when Smith reported that the board was offering $100,000 for “planning” a state network. Smith and the other committee members rejected the plan emphatically, stating that there had already been enough planning. Smith suggested that MICIS start thinking of other sources of money, even looking to see if the universities themselves could fund the program.

At what may have been MICIS’ lowest point, the March 1967 MICIS minutes show that one member suggested MICIS “fold its tent.” Instead, the members used the April meeting to explore the question: “Quo Vadis MICIS?” At that meeting, Smith called for focus, and stressed the need for communication and cooperation among the members. Muelder reported that he had polled faculty at Michigan State and found continued support for the computer network idea. These statements at least affirmed that the universities were still interested. The members decided to continue meeting at one or two month intervals.

Their resolve was rewarded in June when the legislature voted $200,000 for the network. The grant required MICIS to find a matching $200,000 from another source, and was subject to “systems study” and “cost analysis” requirements, which would cause delay and frustration two years later.

The plan brought some complaints from other members of the university community. Wayne State’s Computing Center Director Walter Hoffman said some faculty there were concerned that they were not being kept well informed about the network, and that MICIS activities might deprive WSU of some funds. Smith confirms that there was some distrust, as well as ignorance, about the proposed network at the schools.

“The general university community didn’t know anything about it,” he says. “There was some opposition, almost.”

Despite the distrust, Zinn, Hoffman, and Julian Kateley of Michigan State paid a visit to the National Science Foundation in Washington to search for matching funds. Arthur Melmed, who remained MICIS’ NSF contact for most of the network development period, responded that NSF liked the idea. He stressed, however, that though NSF would look at a proposal, it was not soliciting one.

When MICIS next met, in October, Zinn was ready with a proposal outline, and was named chairman of the drafting committee. The November 3 MICIS minutes record that Zinn reviewed a revised outline and wanted to know if he should take the outline to Washington for a further look by NSF. Smith insisted on the importance of getting a draft done, and the committee set November 20 as a date for a completed draft.

Zinn and the committee worked on the proposal through November, December, and part of January. Members debated how much money to ask for, settling on a figure over $1.8 million, far beyond the matching funds requirement. The 45 page proposal, “Development of a Prototype Network of Computer Services for Self-Instruction and Teaching,” was submitted the 26th of January, 1968. The committee then decided to invite important state senators and representatives to the February MICIS meeting, to be held in Lansing to discuss the proposed network.

The meeting took place on February 2, 1968. The legislators present were members of the Senate and House Appropriations Committees. They included Senator Garland Lane, of Flint, who challenged the proposal to NSF as going beyond a “feasibility” study, which he thought was the intent of the legislature’s grant. He also questioned the “compatibility” of the machines to be linked, and challenged what he thought was proposed kindergarten through high school participation in the project.

The committee tried to assure him, noting that the project was not a feasibility study, but an actual test of networking ideas; that linking differing computer systems was one of the main features of the project; and that the project in no way intended kindergarten or high school participation. Though the MICIS members didn’t know it, this meeting would lay the groundwork for later difficulties in getting the state funds released.

After the legislators left, the committee discussed appointing a director for the network project. Now that they expected to get funds from the NSF, they wanted to speed development by paying someone to direct what had been to this point a volunteer effort. They agreed to appoint a director from nominations made by the schools.

The committee received nominations in March, and by April Smith sought consensus on-the selection of Bertram Herzog, a professor of industrial engineering at the University of Michigan. Herzog was invited to lunch so that the Michigan State and Wayne State members could get to know him better. The committee also heard that a new bill before the state legislature might mean another $200,000 of support.

In May NSF complained about “vagueness and lack of specificity” as well as the amount of money requested in MERIT’s proposal. Aid was very doubtful for that fiscal year. At the same time, MICIS reached a consensus on hiring Herzog as director for MERIT, and he was henceforth invited to all MICIS meetings.

“It was quite important to the development of the project,” Smith says of Herzog’s appointment. “Before that time, it was mostly a volunteer effort.”

With Herzog’s appointment, Smith’s role diminished, though he still had an important part to play. He would be instrumental in getting state funds released a year-and-a-half later, as well as in securing the last state appropriation in 1972. He remembers what seemed like interminable delays and problems, both monetary and technical, in getting the network going.

“There were times when I got as irritated as any state legislator,” he says. He recalls in typically understated fashion his reaction to the final success of the network.

“I do recall a bit of joy when Bert (Herzog) finally told me we had done it.”

The years of Bertram Herzog’s leadership, 1968 to 1974, were ones of progress and excitement. Herzog hadn’t heard specifically about the MERIT project when Allan Smith asked him to be director in 1968, but he quickly became enthusiastic.

“Once I understood what was to be done, I got quite excited about the whole thing. It really was an interesting challenge,” he says today from his office in the Industrial Technology Institute in Ann Arbor, where today he is director of the Center for Information Technology Integration.

Herzog, who received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Case Institute of Technology, took his doctorate in engineering mechanics from the University of Michigan in 1961. After serving as an assistant and associate professor at the U-M, he worked briefly for the Ford Motor Company, then returned to the U-M, where he became professor of industrial engineering and Associate Director for the Defense Department sponsored Concomp Project, which experimented in the conversational uses of computers. As such, Herzog was familiar with recent developments in networking technology. It was as Concomp associate director that he had offices in the Ouimet Building at 611 Church Street in Ann Arbor, where the first MERIT headquarters slowly evolved.

At Ford, Herzog had been a manager for technological innovation. He suspects that his managerial experience had something to do with his choice for the MERIT job.

“It smelled like a similar problem,” says of the task of coordinating the three universities.

Herzog was quickly introduced by telephone to NSF’s Melmed to demonstrate the project’s “gathering momentum,” in the words of the June MICIS minutes. Herzog took over as chairman of the Proposal Revision Subcommittee, with Julian Kateley, Hubbard, and Zinn as committee members, to revise the NSF proposal. That meant listening to NSF and writing to their needs, Herzog says.

“Not only did we hear, but we expanded.”

Meanwhile, the legislature passed, and on July 1 the governor signed, a bill providing another $200,000 for MERIT. The language of the bill stated that the money was to continue “feasibility studies and preliminary preparation limited to higher education only as originally planned and presented to the legislature.” The new money was subject to the same matching funds and other requirements as the previous year’s bill.

In mid-July Herzog paid a visit to NSF in Washington. A week later he sent a memo to MICIS members suggesting ways to make the proposal more specific. Despite this effort, work was still slow, and at the September MICIS meeting, Herzog introduced two of his associates from the Concomp project, Mary Ann Wilkes and Ray Burris, to help with the proposal writing. “She was an outstanding writer. He did the business part,” Herzog says. Herzog expressed hope of having the proposal completed soon after the October meeting.

October came and the proposal was still in the preliminary stages. November 1 became the deadline for a new rough draft. Herzog sought help in three areas: the educational part of the proposal; assistance with computer languages; and an advisory committee to review the proposal. Wayne State’s Hubbard agreed to work on the first task. Zinn, with the help of Michigan State’s Norman Bell, took on the second. The three senior officers, Smith, Hubbard, and Muelder agreed to appoint the review committee.

By the November 12 MICIS meeting, work had progressed enough for the members to conduct a page-by-page review. Herzog now hoped to have it completed by Thanksgiving, and he made all further information due by November 15. In last-minute decisions, the members decided to refer to the MERIT network throughout the proposal, instead of sometimes using MICIS; and they decided to keep the word Prototype in the proposal title. Finally, Herzog asked for the curriculum vitae of the MICIS members and others involved in the project, to be included in the proposal with his own.

The final document, titled “Development of a Prototype Computer Network,” was over 200 pages. It asked $1 million, well over the matching funds requirement, but not as much so as the first proposal. The title, which left out the references to self-instruction and teaching of the year earlier document, reflected the subtle shift in direction the program was taking. The proposal was submitted in December 1968.

Intensive negotiations with NSF about the proposal followed during the winter and early spring of 1969. This resulted in reducing the budget request to $400,000, the minimum required by the state legislature, and earmarking the NSF funds for equipment and personnel. Meanwhile, nervous MICIS members discussed alternatives to NSF funding, just as two years before they had discussed alternatives to state funding. Michigan State’s Muelder suggested that MICIS approach IBM and Control Data Corporation with the proposal. Allan Smith promised to contact the Kellogg Foundation. The members then suggested further improvements to the already submitted proposal, looking forward to a possible NSF site visit.

Positive news from NSF came in May. In a telephone call, NSF’s Melmed suggested that only minor problems remained to be negotiated. Herzog readied a list of immediate tasks, now that funding looked very probable. These were: appointment of the MERIT Associate Directors; selection of a network headquarters site; appointing a project engineer and lead programmer; selection of hardware; and appointing technicians. Above all, Smith stressed the importance of getting on with building the network and not diluting energies of the soon-to-be-hired network staff.

“The people who wanted applications wanted more attention,” Smith says, but it was obvious that applications were useless until there was an operational network. Also, it was harder to get the state to support applications development, according to Smith.

Despite the enthusiasm and energy generated by May’s hopeful news, two months passed before NSF officially granted the funds. At the June 30, 1969, MICIS meeting, Herzog announced that Michigan’s members of congress would be officially informed of the grant the next day, and MICIS the day after that. Robert Hubbard informed the committee that he had already contacted the Joint House and Senate Appropriations Committee of the state legislature, asking them to prepare to release state funds, but that so far he had had no reply.

There were still some obstacles to securing the state funds. Robert Hubbard sent the official forms requesting the funds’ release on July 14. On July 17, William Copeland, Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, sent a letter to State Budget Director Glenn Allen stating that he believed the legislature’s criteria had been met, and suggesting a joint meeting to discuss the matter and authorize the release. Hubbard received a copy of this letter and understood it to be ” . . . simply a confirmation of what I already learned from Mr. Endriss, viz., that the State is ready to release the $400,000 . . .”

Difficulties began on August 8 when Glenn Allen sent a letter to Copeland saying legislative system study and cost analysis requirements had not been met. He referred to objections raised by Senator Lane at the MICIS meeting of February 2, 1968. He also pointed out that the original $200,000 appropriation had not received matching funds at that time, and that the 1968 appropriation of $200,000 had not even been passed by the legislature. Allen blamed the “considerable confusion” on authority being divided between the executive and legislative branches.

On September 4, the Senate Appropriations Committee met and decided officially that the funds could not be released. Some members reiterated the concerns expressed a year and a half before. On September 11, Allen sent Smith a letter advising him of the committee’s opinion, and enclosing a report constructed from notes taken at the February, 1968 gathering. The committee requested a meeting between MERIT, the budget office, and themselves. The meeting was held later that fall. The Senate passed a special authorization to release the funds on December 18, 1969, shortly before the 75th legislature adjourned. Final release by the budget office didn’t come until January 14, 1970.

Herzog today jokes about the long delay in getting the state funds released. “That’s obviously well forgotten,” he says laughing. “I don’t remember it as a major trauma.”

He points out that the MERIT Board often got more time before the state legislative committees than some state colleges. “There was a vogue at the time of, “we’re gonna get these data processing types shaped up,” he says. “We were, of course, pleased that they would spend that much time on us.”

While the struggle to clear the state funds went on, Herzog lost no time starting to build the network. By the August 8th MICIS meeting, Herzog had hired Eric Aupperle, the current president of MERIT, to be senior engineer starting September 1, 1969. Aupperle who had received his professional engineering degree from the University of Michigan in 1964, was a research engineer at the University of Michigan Cooley Electronics Laboratory. At MERIT, his job would be to provide the technical solutions to connecting the three diverse computing systems at the member universities.

“It was clear that we needed someone who had electrical engineering, circuit design capabilities,” Herzog says today of his choice of Aupperle. “There was a lot of innovative stuff to be done.”

Aupperle immediately began looking for hardware to make the network operational, and Herzog busied himself screening chief programmer applicants. As well, Julian Kateley and Karl Zinn were named Associate Directors for Michigan State and the University of Michigan at the September MICIS meeting, and computer science professor Seymour Wolfson was named Associate Director for Wayne State. Herzog today credits “the power of positive thinking” for his confidence to proceed while the money issue remained undecided.

To find suitable hardware chiefly a communications computer capable of connecting the three universities’ diverse systems Aupperle sought proposals from commercial manufacturers. At the same time, he and others visited the three universities’ computing center directors to prepare them for MERIT’s arrival.

One such meeting took place on November 26, 1969 between Aupperle, Herzog, Frank Westervelt, and Professor R. C. F. Bartels, then head of the University of Michigan Computing Center. Also present was Alfred Cocanower, who had recently been hired as head software developer for the project. The MERIT staff briefed Bartels on their attempts to find a communications computer. They also discussed the Computing Center’s impending move to new headquarters on the University of Michigan’s north campus, and the limited floor area at the present site, the old North University Building on the central campus. Though Bartels stressed “minimum interference” with the host, Aupperle was pleased that Bartels raised no objection to MERIT’s using the IBM’s multiplex channel for its communications computer interface.

“In summary, the meeting was most satisfactory from our point of view!” Aupperle wrote in a memo about the meeting.

By January 9 of 1970, the date of the first MICIS meeting since September, requests for hardware bids had been sent to 13 manufacturers, with responses due by January 20. Herzog reported that the project was behind schedule, but that he expected delivery of the first communications computer in early July.

By the April meeting, things had changed. Herzog reported that none of the vendors’ responses to MERIT’s solicitation ideally suited MERIT’s needs, nor did they capitalize sufficiently on the technical skills already available at the three MERIT universities. Herzog then announced a major new plan, to purchase three minicomputers and negotiate a contract with a commercial hardware vendor to build special interfaces to the universities’ mainframes. The vendor would be given a choice between a DEC PDP-11 or an Interdata computer. Cost for hardware, installation, and testing was expected to be $300,000. “That was a challenge,” Herzog says today of the decision to abandon the original plans for buying off-the-shelf communications equipment. He admits it slowed the schedule, but says, “One learns after a while a certain sense of reality about what one can expect from these things.”

The new plan meant that estimated installation dates had to be revised, with the earliest date for installation of the complete system now put at January 1971. The picture was clouded, however, by the construction of the new University of Michigan Computing Center and the installation of a new computer at Wayne State. A latest possible date for installation of the system was set at June 1971.

While hardware development was being slowed, software development proceeded apace and was expected to be complete by August 1970. Herzog hoped reports on the software development could be sent to various computer conferences and technical journals by May of the next year.

June of 1970 was a busy time for MERIT. It had now largely taken over the offices on the top floor of the Ouimet Building at 611 Church Street in Ann Arbor as the Concomp project ended. Eric Aupperle recalls that the headquarters consisted of several offices along the walls of the top floor and a large area in the center of the building that served as a work area and tab. MERIT was now big enough that Aupperle had to issue an organizational chart clarifying staff responsibilities. The chart included 30 people, though as Aupperle was careful to point out, many were employed only parttime by MERIT and were local staff at the three universities. Staff at the MERIT Church Street headquarters numbered about 10.

June also brought the very important step of letting a contract to Applied Dynamics Division of Reliance Electric in Saline, Michigan, to build the communications computer systems. Each would consist of a DEC PDP-11 computer, dataphone interfaces, and host interfaces. The cost was to be slightly less than the $300,000 originally budgeted. Though another firm also submitted an acceptable bid, Applied Dynamics was chosen because of its geographical proximity to MERIT’s Ann Arbor headquarters.

Also that month, Alfred Cocanower sent a memo to Herzog and Aupperle listing the fairly modest equipment needs for the MERIT staff. These were one 35ASR paper tape machine, two Datel 2741 compatible terminals, and an IBM 029 keypunch. Each of the Datels also required a telephone circuit, and Cocanower recommended that one of the circuits have six jacks to that the machine could be moved. The two terminals were apparently rented by June 26, as a memo on that date from Cocanower specifies the rooms where they were to be kept.

July brought more good news. Herzog reported to the MICIS meeting that assembler software for the PDP-11 had already been written and was running on the IBM 360/67. This was largely the work of Cocanower’s staff, which consisted of Wayne Fischer, Brian Reed, and two junior programmers. The assembler worked the first time it was run on a PDP-11, even though it was entirely written before the first PDP-11 was delivered. As another example of the technical work that was going on, the July MICIS minutes record that two major technical issues being worked on by the MERIT staff were job queuing and simultaneous processes. Herzog stated that he had specifically instructed the staff to avoid ad hoc solutions to these problems.

An August 1970 memo to Herzog, Aupperle laid out what progress he expected on the network. He anticipated that Applied Dynamics would have completed development and testing of all equipment by March or April of 1971, and have all three communications computers installed by June of that year. As well, he expected a connection between the three communications computers by June. He even hoped that some inter-host traffic might be possible, allowing a message to be sent by University of Michigan President Robben Fleming to Michigan State University President Clifton Wharton. He expected a “truly operational” network by June 1972, a year later.

“I have every expectation that this goal is a feasible one. Our secondary assignment should be the planning for and possible early development of an expanded network. Collectively, these two tasks will keep us quite busy next year,” the memo reads.

Herzog reflected these hopes in an October 20, 1970 speech to the Michigan Council of State College Presidents when he suggested that “especially patient customers” might be able to use the network by July I of the next year. At the same meeting, he told the college presidents that the biggest technical problem currently facing the network staff was working out network service routines.

“The problem of host to host or user program to user program communication plagues not only ourselves but also other network researchers,” he said.

Applied Dynamics did not deliver the first communications computers by early January as hoped, once again putting hardware development behind schedule. However, in a January 20, 1971 memo detailing expected hardware installation dates for all three universities, Aupperle still expected final acceptance testing by May 28, making a July 1 operational date feasible.

Hardware delivery finally got under way in March, coinciding with the University of Michigan Computing Center’s move to its new headquarters and MERIT’s subsequent move into the Center’s old offices in the North University Building. A March 24 memo from Aupperle explains that Applied Dynamics would deliver one of the PDP-11s, with host interface, to the old Computing Center April 1, for use in testing. The PDP-11 system then at 611 Church was to be taken to the Applied Dynamics plant in Saline, MI on April 1, fitted with three telephone interfaces, and later delivered to Wayne State. On April 15, the PDP-11 that had been delivered to the old Computing Center would be taken back to Saline, and redelivered to the new Computing Center in early May.

By June 1971, when both Aupperle and Herzog had hoped to have the communications computers linked, some hardware had been installed at all three universities. On June 24 MERIT moved into its new headquarters in offices overlooking the loading docks in the North University Building. Eric Aupperle recalls that many people coming into the building could not find the obscurely located offices. To remedy the problem, a large blue and white sign saying “Merit Computer Network Project” was constructed and hung outside by the loading dock.

June also brought the announcement that Alfred Cocanower, who had led MERIT’s software development, would leave the project at the end of November. In order to make the best use of Cocanower’s talents before he left, Herzog relieved him of responsibility for supervising the programming staff and asked him to work on new system designs.

Herzog also announced in June that he was forming the MERIT Director’s Advisory Committee. The committee would include the three universities’ computing center directors, the three network Associate Directors, Aupperle, and Herzog.

“This was a very good mechanism for people to get to know each other,” besides providing valuable input to the director, Herzog says.

While all of this technical and organizational preparation was going on, the financial picture of MERIT looked gloomier. The problem divided into two parts. First was the necessity of asking the state for funds for the 1971-72 fiscal year. Second was the imminent end of the funds that had already been granted from the state and NSF.

At the March MICIS meeting, Herzog had reported that MERIT’s budget proposal for the 1971-72 budget year had been submitted to the state. It requested $400,000, $200,000 of which was for development of a “satellite” facility to link at one of the smaller schools in the state to the network. Herzog admitted that the satellite portion of the request was unlikely to pass, and Robert Hubbard doubted MERIT would receive more than $25,000 to $50,000 over the next year.

Herzog then presented the current budget, which showed that MERIT would have a little over $160,000 left after the June 30 end of the fiscal year. This would support the network for an additional six months, if there was no help from the state, Herzog said. Hubbard asked Herzog to draft a budget based on minimum funding from the state for the next fiscal year.

Herzog provided the minimal budget at the April MICIS meeting. It called for cuts in personnel, and giving back some rented telephonic equipment. Herzog then estimated that with the new budget the staff could carry on “continuous, but minimal” activity over the entire next fiscal year. He was most concerned about keeping the highly specialized staff. To add to the gloomy financial picture, Herzog reported he had recently visited NSF, and MERIT could expect no immediate help from them.

The austerity budget presented some very real problems to the upcoming tests of the network. One of these problems concerned the four 201A Data Sets and the 801C Automatic Calling Unit rented from Bell Telephone and installed at each university. The austerity budget meant that the automatic calling units and two of the four Data Sets at each university could no longer be rented. In a May 19, 1971 letter to Mr. G. R. Harrington, a Vice President of public relations at Bell, Herzog asked for a year’s “grant in kind” use of the telephonic equipment. An later memo by Herzog records that Bell denied the request.

With at least some of the hardware in place, it was still possible to test the software. The six months from July to December 1971 saw a series of steps which brought the network into being, though a truly operational status was still some ways off.

The first step was to connect two of the communications computers. This happened on July 8 between the PPD-11s at the University of Michigan and Michigan State. A copy of some output from this session shows the excitement of the testers.

“THIS IS GREAT! ! ! ! ! ! ”

“IT’S GREAT TO SEE SOME HARD COPY AFTER ALL THE WORK WE’VE DONE”

“I THINK BH (Herzog) WOULD LIKE TO SIT DOWN AND DO THIS WITH YOU.”

Though these tests showed that the communications computers could talk to each other, they still didn’t prove that one host computer could connect to another.

The next big step occurred on the night of October 26. Aupperle and his staff signed on to the University of Michigan host computer, connected through it to the PDP-11 communications computer, and through the PDP-11 reconnected with the host computer. Though this test did not actually use the network in the sense that it connected two different hosts, it did show that the interface between one communications computers and a host worked.

Herzog was excited enough about this achievement send a letter to several people the next day. “I have some good news I wish to share with you immediately!” he wrote. Besides explaining what had happened, Herzog explained that hardware testing had been concentrated at the University of Michigan because of its proximity to Applied Dynamics, but that he hoped to see the test easily reproduced at the other universities.

In an even more important but less heralded step, a University of Michigan to Wayne State host-to-host connection was established on November 16. This test was really in preparation for a more public demonstration of the network being planned for the next month.

That demonstration came at 12:20 a.m. on December 14, 1971, when someone at the University of Michigan used the network to sign on to the IBM computer at Wayne State University and run a computer graphics program. The program computed the points of a parabolic curve inside a triangle displayed by the University of Michigan computer. As the user changed the angles of the triangle, the program at Wayne State computed the points of the new curve and displayed it inside the changed triangle. A university news release prepared before the actual demonstration called the connection “a milestone in higher education” and an “historic event.”

The process was clumsy compared with network communications today, as was shown in a film of the same demonstration prepared by Herzog a few weeks later. In the film, Herzog sat at a DEC 338 computer graphics terminal equipped with teletypewriter and cathode ray tube. He signed on to the University of Michigan’s IBM 360 full duplex mainframe much as users do today, except that he dialed directly into the mainframe. The familiar MERIT “Which host?” prompt, part of today’s MERIT terminal support, would not be invented for four more years.

Once connected to the U-M’s IBM, Herzog had to run a special program, RUN KlY2:NETMOUNT, to connect to the U-M’s PDP-11 communications computer. He then chose the parameter *QUEUE* as a way of referring to the network. Next he had to issue the command DST=WS to tell the communications computer he wanted to connect to the communications computer at Wayne State. Once connected there, he had to $RUN KIY5:C and enter *QUEUE*, the name he had given to the network, to keep the U-M computer from “consuming” the Wayne State signon information. All of this information was printed on the Teletype machine, not the terminal screen.

Once signed on to the WSU machine, Herzog typed $RUN and the name of the parabola computing program, which had been written by one of his students. He was careful to $SET PREFIX=OFF, a command familiar to MERIT users today, to prevent the system prefix from interfering with the program calculations.

Finally, Herzog issued an end of file command to the WSU machine so that he could run the U-M half of the program. That part of the program displayed a triangle on the cathode ray tube. Herzog used a light pen to point to an angle on the screen and move it. The new triangle was then displayed by the U-M computer. Then Herzog used the light pen to select the word compute, which was also displayed on the screen. The information was transmitted across the network to the computer at Wayne State, where the points of the parabolic curve that fit the new triangle were computed, transmitted back across the network, and the curve displayed inside the triangle. Herzog could, of course, change the triangle again and compute a new curve.

This demonstration affirmed, with considerable fanfare, the system’s workability, but by no means meant that the network was operational. In fact, host to host connection to Michigan State from either of the other two hosts would not be available for another nine months.

While Aupperle and his crew worked on the remaining technical problems, MERIT’s finances came up again at the January, 1972 MICIS meeting. MERIT had not received any funding since the release of the original state money two years previously. The previous year’s budget request was still pending in the legislature. Herzog reported that MERIT would be out of funds by June 30 if the legislature did not vote new funds by then.

At the end of June, Herzog closed the books on the original $800,000 that MERIT had received from the state and NSF. In July, MERIT went on a no-funding budget while it waited for the legislature to act. The network survived with help from the universities, which had agreed support MERIT if there were absolutely no state or federal support. The state legislature finally granted MERIT an additional $200,000 in the summer of 1972, though the money was still not available by early August. Merit had survived with no new funds from July 1971 until this aid became available. Though a request had already been submitted for the next fiscal year, the 1972 aid proved to be the last the state would give.

Meanwhile, a major internal question moved toward resolution. Since the earliest days, MICIS members had worried about the effect of unequal traffic flow on the network. If one host was used more than another over the network, the less used host would incur a deficit. There was no procedure for settling such accounts, and more importantly, computing center directors might limit network use to avoid financial loss. Such limitations were inimical to the network.

“That was a major, major problem for us,” Herzog says today. He adds, “There was no incentive to give away computer time. We had to overcome that and that took a lot of effort.”

It wasn’t until the Director’s Advisory Committee addressed the issue that it was solved. By late November, 1971, shortly before the first successful host to host connection, they had agreed to an accounting procedure that would encourage network use. Essentially, it allowed each host to charge local customers for all services, including services received through the network from another host, at rates set locally. At the same time., each host computing center could charge each other host computing center at its own rates for services flowing to that host. The agreement allowed for cash settlements of deficits, though in practice these deficits were forgiven in the early years of the network. The agreement was officially accepted in September 1972.

There was also steady, if undramatic, progress on building the network after the initial 1971 public demonstration. By April, network service between the University of Michigan and Wayne State was almost daily, though limited to afternoons. This service became available on a nearly continual basis after July 1. From July through September, there were a total of 1543 successful connections, transmitting over 16 million characters of data, according to the November 1972 issue of On Line, a magazine begun by Karl Zinn earlier in the year.

Problems remained at Michigan State, where the network had to connect to an entirely different operating system than those at the University of Michigan or Wayne State. Finally, on October 2, 1972, the Michigan State node was tested and the network was complete. It came just in time for the EDUCOM conference October 11-13, which was held in Ann Arbor at MICIS’ instigation. That conference included continuous, on line demonstrations for the network, as well as presentations by Herzog and Aupperle, according to Zinn’s On Line.

With the completion of the Michigan State node, the main network developmental work was done. MICIS members now discussed holding a dedication, which they planned first for early January 1973, then for March, then May. They debated whether the presidents of other state colleges should be invited (they were), who should be seated with whom, and what were the purposes of the dedication. They agreed the dedication would strengthen ties with state government, from which MERIT still hoped to gain funding.

The ceremony took place May 15, 1973, in the Centennial Room of the Kellogg Center on the Michigan State campus. The network was “presented” by William Copeland, Chair of the House Appropriations Committee, and Dr. Thomas Owen, Assistant Director of NSF. Allan Smith “accepted” the network. The main speech was given by Owen, who called MERIT ” . . . an outstanding achievement in developing an integrated linkage of computer centers and, as such, a prototype of future networks, according to a report of the events in On Line. Owen’s speech was followed by a demonstration of the network.

The network’s completion and its formal dedication raised the question of MICIS’ future. At the May MICIS meeting, Herzog recommended that MICIS expand to include the other state schools, and that it return to its broader, original role of promoting institutional cooperation in information exchange. He also recommended that the highly dependent relationship between MICIS and MERIT be severed. MICIS expansion did take place that year, and since the mid-1970s the MICIS committee has been a subcommittee of Michigan’s Presidents Council of State Colleges and Universities. The Merit Computer Network president remains an ex officio member of MICIS.

Herzog resigned the MERIT directorship in 1974 and it was taken over by Aupperle. Looking back at the early days, Bertram Herzog says his most challenging task was fostering cooperation among the three schools. “They had never had the need to cooperate in that depth,” he says. “I think we all felt good that we got it done.”

What of his faith that he could accomplish the never before attempted task, linking three diverse computing systems so that they could work interactively? Herzog smiles.

“It was certainly viewed as an experiment at the time,” he says. “You had to believe, but you couldn’t know.”