CHAPTER 1

Change happens when the right collaborators and the right leaders come together at the right time for the right reason. The time is now.

Our state, and our nation, face serious challenges related to access to information, economic development, workforce and talent retention, the homework gap and more. Access to broadband is critical to improving the quality of life and promoting prosperity in our region.

National Statistics on the Digital Divide

- Over 3 million students, or about 18% of students in the U.S., lack internet access at home.3

- More then 21 million Americans lack broadband access, according to a 2019 Federal Communications Commission report.

- A study from Microsoft paints a starker picture, showing that 162.8 million Americans do not access the internet at broadband speeds.

Michigan Statistics on the Digital Divide

Michigan ranks 30th in the nation for broadband availability.1

At least 368,000 homes in Michigan lack access to broadband. This equates to 27% of households in the state with school-age children.1

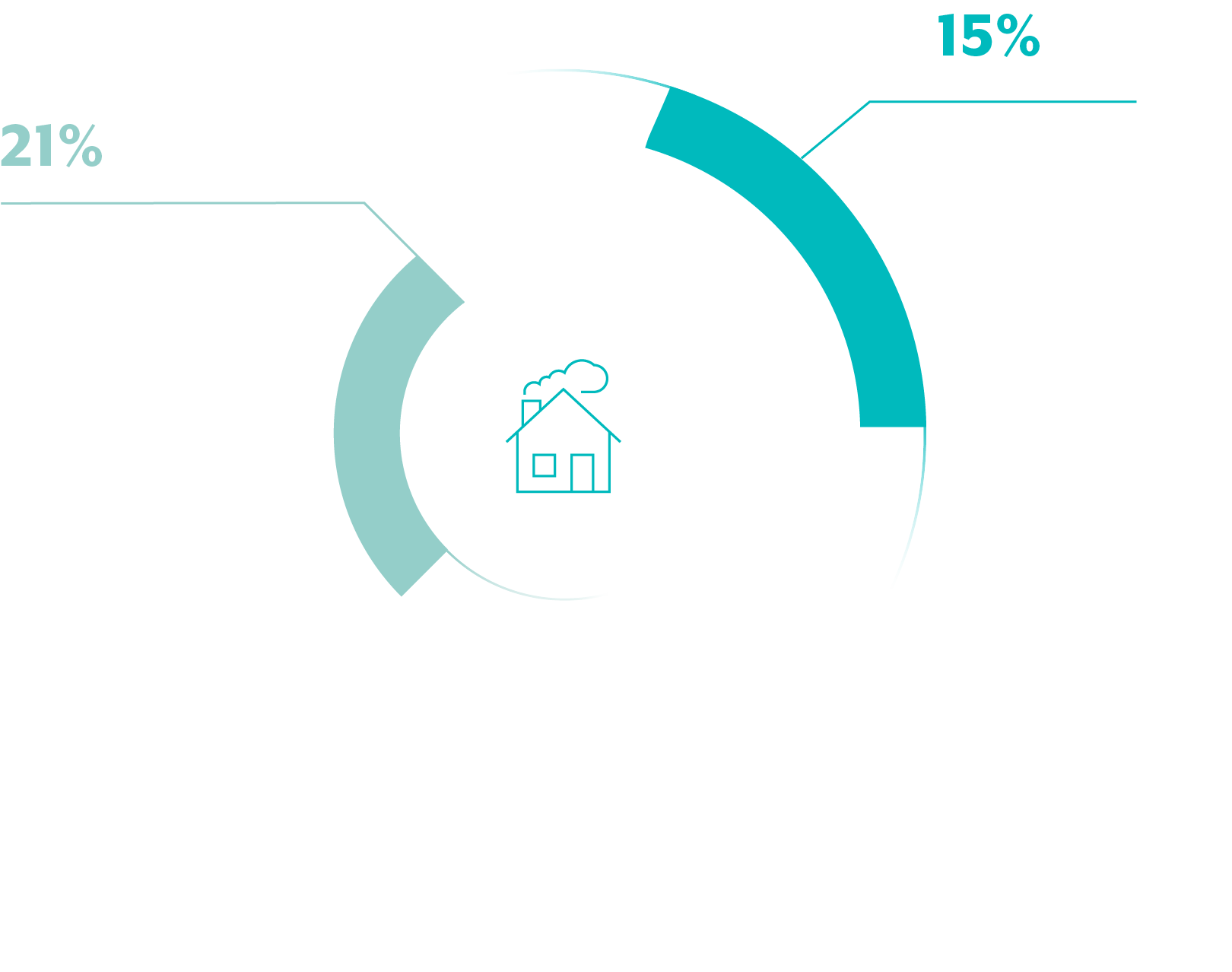

Of the 1,773 municipalities in Michigan:

- 367 (21%) have no broadband access at all.

- 659 (37%) have more than half of their households lacking broadband access.

- 376 (21%) have complete broadband coverage for all households.6

2 million (48%) of Michigan households do not have access to more than one broadband provider, meaning no competition or choice exists when they look for a service provider.1

5.7 million (57%) of Michigan residents are not using the internet at broadband speeds.

A Crowdsourced Solution

Solving the broadband access challenge requires the shared vision and partnership from a coalition of stakeholders. Public, private and nonprofit organizations; government agencies; educational institutions; regional broadband champions; policymakers and others are critical for regional network success.

This crowdsourced framework will serve as a regional network primer and the basis for planning your community’s road map. Contained within, you’ll find overviews on policy and technology, community success stories, links to myriad resources and planning tools from national broadband leaders, and a phased plan for building a community network.

Contributing organizations include:

A complete list of contributors and peer reviewers can be found on chapter 11.

This framework has been designed as a living document. We welcome additions to the knowledge base we have started. Should your organization be interested in contributing to a future version of the framework, don’t hesitate to contact the contributors.

Information is the great equalizer, and together, we can make great strides in eliminating the social divide for our students, neighbors and communities.

Access to and use of the internet has become an integral component of everyday life in the 21st century. Digital information has reshaped how individuals participate in nearly every dimension of society. It is imperative that communities leverage broadband network access to eliminate the homework gap and improve education, socioeconomic equality, telemedicine, public safety and economic development to maintain and grow the quality of life for their residents.

At least 368,000 homes in Michigan lack access to broadband. This equates to 27% of households in the state with school-age children.1 Low population densities and rough terrain present low returns on investment for commercial providers to serve these rural communities. Additionally, flawed methods of data collection by the Federal Communications Commission produce inaccurate and overestimated connectivity information, which acts as a disqualifier for many federal, state and foundation funding sources.

A parallel between broadband access inequality and the availability of electricity in the 1930s can be drawn. As electricity became common in cities, rural communities had little access—less than 10% of rural U.S. households had electricity. In 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt introduced the Rural Electrification Act, which provided both a national strategy and funding to build electric infrastructure in rural areas. Although it is unlikely that broadband will be federally declared a public utility, it is clear that like the 1930s electrification of America, new approaches are needed to bring digital equality to all to close the digital divide for communities left behind.21

The suggestions contained within this framework are some of many potential ways to help alleviate the digital divide. Public-private partnerships are critical for improving access to information and lessening the homework gap. The forthcoming document is merely one approach of many that communities should consider when exploring a regional network. Numerous communities in Michigan and throughout the United States have achieved significant progress. A handful of these success stories are contained in the Community Success Stories section of this document.

Broadband is defined as a high-speed internet connection that provides a user the capability to quickly upload and download high-quality video, data and images. Current federal standards for broadband are defined as connections providing 25 megabits per second for downloads and 3 megabits per second for uploads, though this standard has not been adjusted since 2015.2 Technology to deliver this connection can include any combination of wireless, satellite, fiber, DSL and cable services, among others.

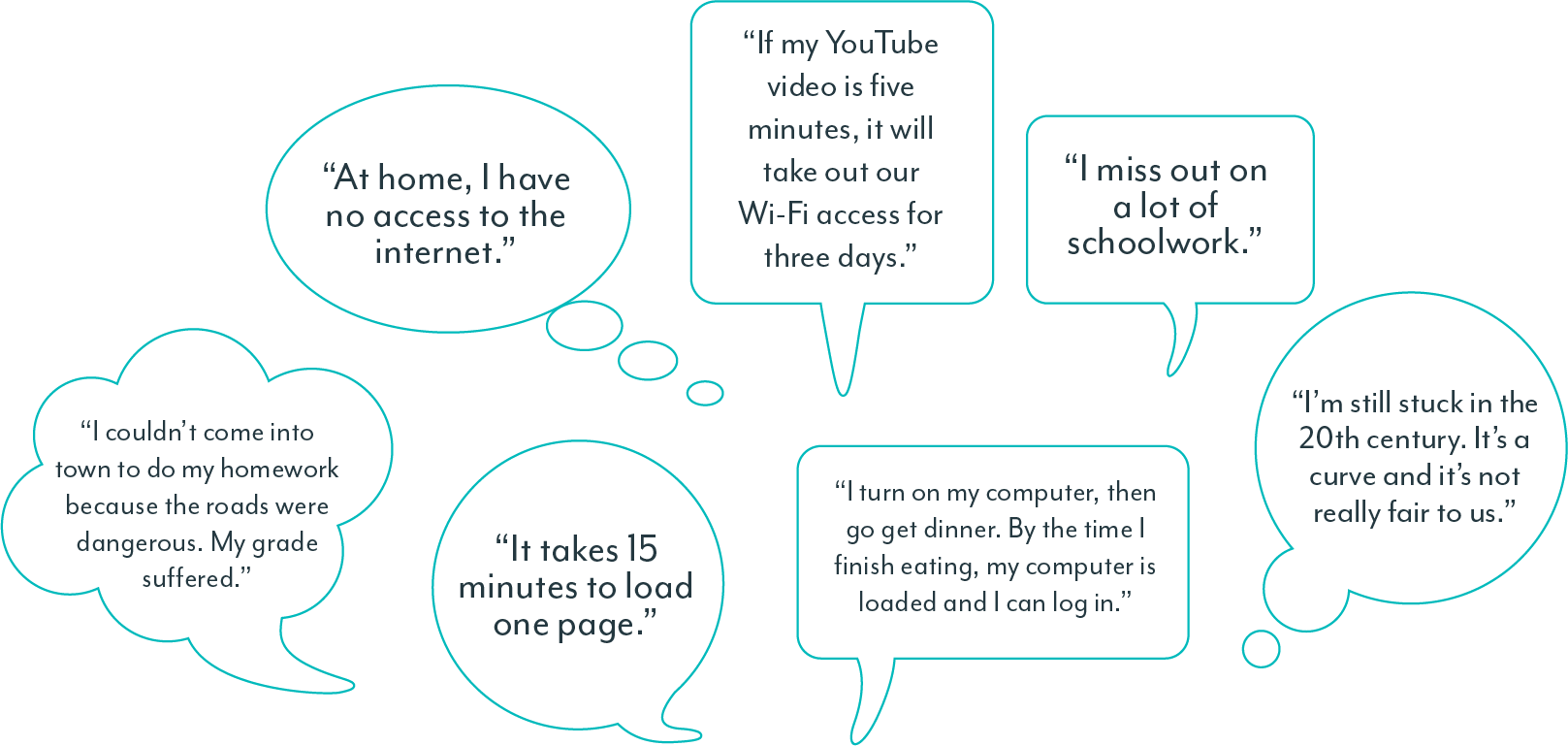

Digital inequities are prevalent in communities across the country. Over 3 million students, or about 18% of students in the United States, do not have internet access at home. In 2009, the FCC’s Broadband Task Force3 reported that nearly 70% of teachers assign homework requiring connectivity. This leaves many students in Michigan and the nation at a great disadvantage. A recent study from the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that students without internet access score lower on standardized tests than their peers who do have access. For example, eighth-graders without home internet access scored 9% lower on reading assessments and 10% lower on mathematics assessments.19

A lack of home connectivity for students has required some creative approaches to academic achievement. Many schools provide 24-hour Wi-Fi access in their parking lots so that parents can drive their children back to school at night to complete homework from the car. Given Michigan’s harsh winters, roads are closed or are too dangerous for this solution to be a viable option for much of the year, in addition to the strain this puts on family schedules.

Some areas do not have even basic cellular connectivity, so that many students complete their homework along the side of the road near the cellular towers along their route home from school. In some communities, even this level of access is unachievable.

Modern lesson plans are designed for students with broadband. Rural teachers are required to reverse- engineer assignments so they can be completed using strictly printed materials. Some teachers report preparing two lesson plans, one for those with connectivity and one for those without. Other teachers report forgoing lesson plans with connectivity requirements entirely.

The impact of connectivity is not limited to the homework gap. Broadband is critical to a community’s ability to thrive and remain competitive in economic development and talent retention. It has been demonstrated that broadband penetration drives economic growth in terms of rising employment rates, the number of businesses established, employment opportunities and population growth.4 Rural areas experience increased community involvement, engagement and participation when internet connectivity is available.

BROADBAND FIBER within a neighborhood has also been shown to increase median home values by as much as 7%.5

According to the Michigan Consortium of Advanced Networks Broadband Roadmap Report1:

Communities without access to real-time data suffer 25% higher rates of injuries and crime.

Having a home broadband connection gives households an estimated economic benefit of $1,850 a year.

Farmers with broadband enjoy a 6% increase in farm revenue, on average.

According to the Wireless Innovation for Last Mile Access (WILMA) report, nearly 40% of rural America lacks access to broadband.2

According to the WILMA report, nearly 40% of rural America lacks access to broadband.2 Connectivity, even via wireless networks, requires access to a backbone fiber-optic network. In Michigan, rough terrain, including forests and dense substrates, makes the deployment of infrastructure—fiber-optic cables—both difficult and costly. Nearly 70% of Michigan is considered rural, which makes the challenge sizable. Wireless technologies are challenged by dense foliage and rolling topography. Low population densities make the economic return on investment problematic for commercial providers. Some rural areas of Michigan house as few as 2 to 20 people per square mile. Often, an organization cannot earn enough revenue to justify the costs of building a fiber connection to rural communities.

Building a last-mile Fiber-To-The-Home (FTTH) network is a costly endeavor. The availability of broadband within a region carries significant weight when the federal government and foundations award funding. Current household access data collection has challenges that include the granularity and level of measurement, the use of data (such as FCC Form 477 filings) that was not primarily collected to measure broadband availability, and the overreliance on internet service providers as the major source of the data. FCC measurements are aggregated to the census block level, which often misrepresents the availability of broadband. If one home within a census block has access to broadband, the entire block is counted as served. Some for-profit ISPs that are not rooted in the communities they service have incentives to overrepresent the number of residences they connect. Future competition will be limited, should an ISP someday achieve positive returns by expanding into a rural community.

These challenges can be overcome by collecting on-the-ground, consumer-sourced data, as proposed by the Michigan Moonshot. (See chapter 2 for more information.) The planning section of the Phased Action Steps provides information on approaches to funding and financing a community network.

The definition of broadband has evolved over the years, but the current colloquial definition is an internet connection sufficient to support modern networked applications. From a quantitative perspective, three attributes are important: 1) bandwidth, 2) latency and 3) data caps.

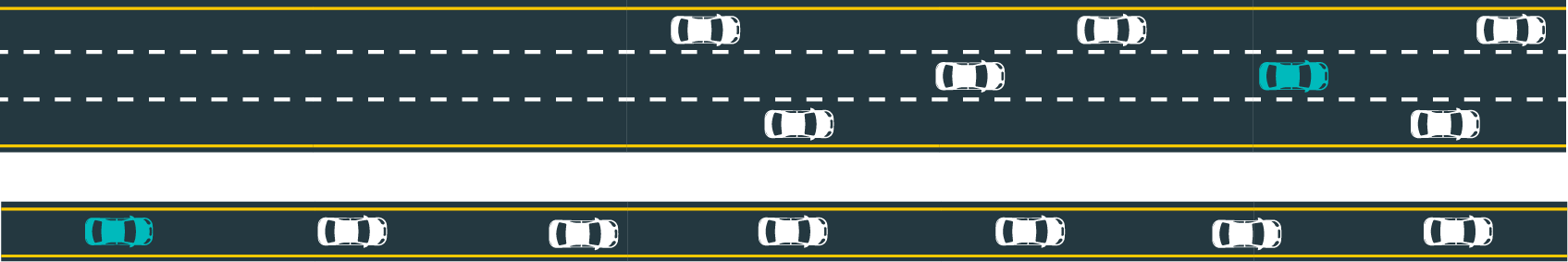

When visualizing bandwidth, or broadband speed, it may help to think of an internet connection as a system of roads. If there is only one lane and a lot of traffic, it will take a long time for a group of cars to reach their destinations. But if more lanes are available, the same group of cars can reach their destinations much quicker.

Bandwidth:

Broadband speed is defined by the FCC as 25Mbps download and 3Mbps upload13, though this threshold was established in 2015 and has become outdated. A more realistic standard should be 100 Mbps symmetrical upload and download speed. While previous broadband standards prioritized download speeds, users are no longer solely “consumers” of data. Today, consumers are just as likely to be data producers. From uploading large data files for work, to cloud backups of home computers, to remotely viewable home security cameras, upload speeds are just as important as download speeds. As such, modern broadband standards should be symmetric for both downloads and uploads.

Latency:

Latency is a different kind of speed. This is the amount of time it takes a single car—or piece of data—to travel from one end of the road to the other.

If you exceed the amount of data you are contractually allowed to use (similar to mileage on a leased vehicle) you can be severely penalized.

When it takes too long, real-time applications such as a voice conversation become delayed and problematic. Broadband connections must remain below 100 milliseconds to support real-time applications.

Data Caps:

For data caps, an analogy can be drawn to leasing a vehicle: If you exceed the miles you are contractually limited to, you are substantially penalized.

Broadband connections should not have data caps. Or if they do, the caps should be high enough to meet household needs without incurring overages. A modern broadband connection should allow for 100 Mbps download and upload speed at minimum, have a latency less than 100 milliseconds and have no data cap.

- More then 360,000 households in Michigan don’t have access to broadband.

Of the 1,773 municipalities in Michigan:

- Michigan ranks 30th in the nation for broadband availability.1

- 5.7 million (57%) of Michigan residents are not using the internet at broadband speeds.

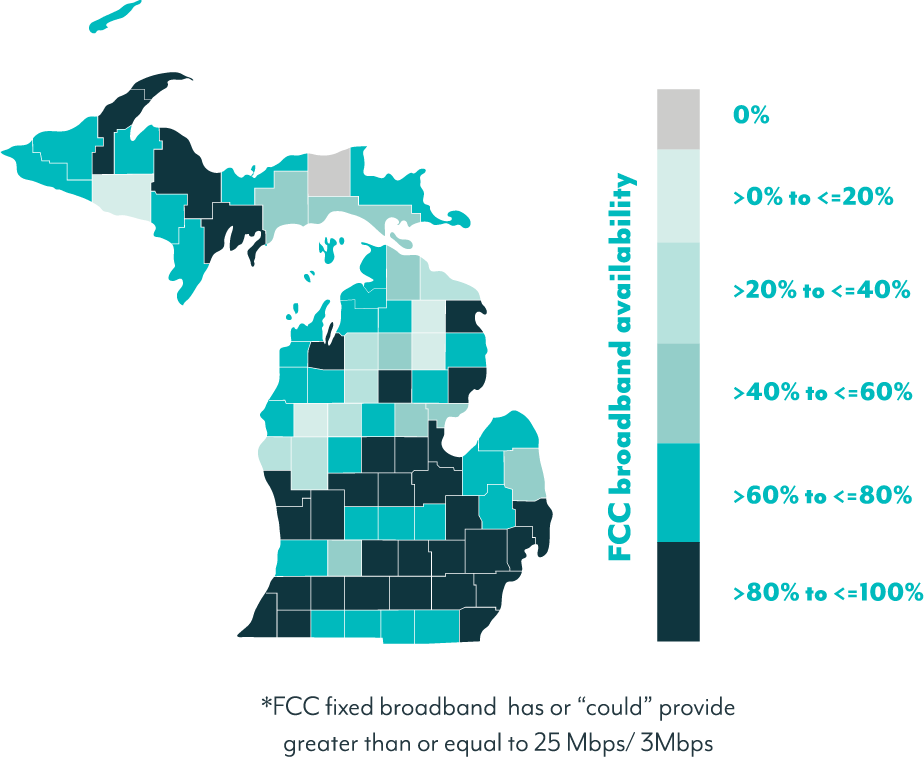

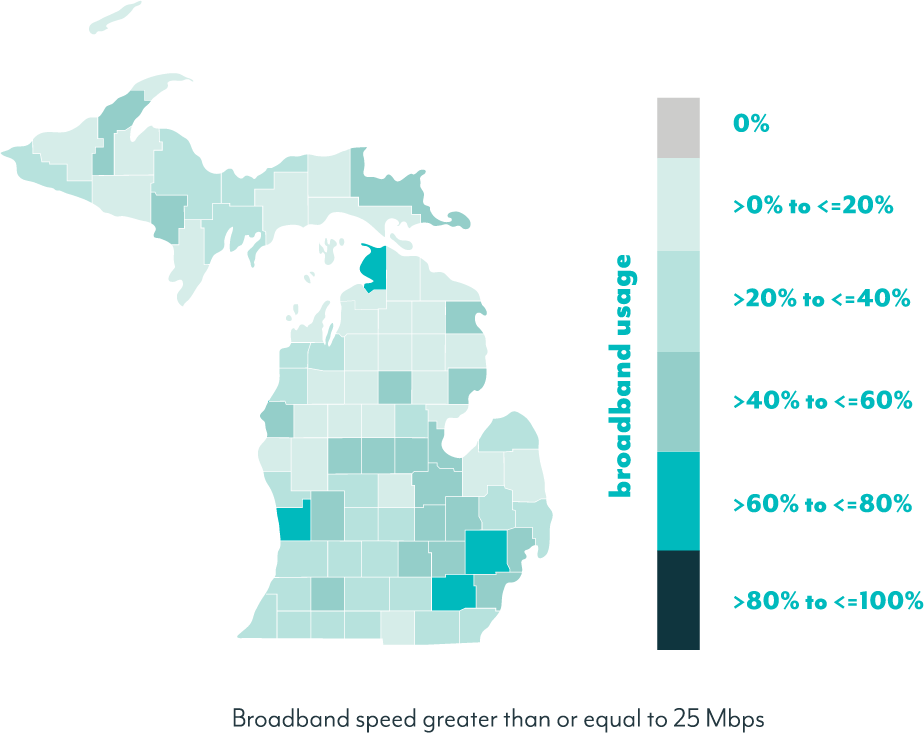

Maps showing FCC fixed broadband availability and broadband usage based on Microsoft data

FCC indicates broadband is not available to 969K people

Microsoft data indicates 5.7M people do not use the internet at broadband speeds